True Blue?

Saturday, 1st June 2013

Forgive me, but I'm going to go all philosophical on you. I'm intrigued by the meaning of the question "What am I listening for?", for within it lies an ambiguity which strikes at the very heart of what we do when we sit down and listen to our Hi-Fi.

Forgive me, but I'm going to go all philosophical on you. I'm intrigued by the meaning of the question "What am I listening for?", for within it lies an ambiguity which strikes at the very heart of what we do when we sit down and listen to our Hi-Fi.The question can have at least two meanings:

The first can be restated as "What am I listening out for?" The second can be restated as "Why am I listening?"

The distinction is an important one. Let's tease this out a bit more.

If we sit down to compare a new cable upgrade or piece of hardware, we may often ask ourselves the question "What am I listening for?", but depending on whether we ask it in the form of 1 or 2 the results can be tellingly different. If we sit and listen according to the first meaning - "What am I listening out for?" - we can easily become trapped in the details of other questions such as "Is the bass tighter on that one?", "Is the treble sweeter?", etc, etc. In fact, it is so easy to become over-focussed on the details that we miss what we are really looking for, and that's the answer to the question "Which sounds best?" How do we answer this then?

If we follow the meaning of the second question - "Why am I listening?" - we come closer to a solution. "I am listening to hear which component, cable, etc, sounds best". And how do we judge this? The only way we can; by listening to the music and noticing, almost subconsciously, which engages us the most, which is the most musical. It all comes back to musicality.

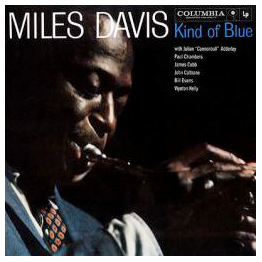

I was reminded of all this when I recently paid a visit to listen to Russ's system. The initial intention was to compare three different versions of 'Kind of Blue' by Miles Davis. I had just purchased another copy as part of a box set and we wondered how the different versions compared. So I sat there, ready and prepared to listen for any clues or subtle changes in the presentation that would differentiate the recordings. And I listened. And I was completely engrossed. So engrossed, in fact, that I forgot that I was there to make comparisons.

The irony was that in 'forgetting to listen' I had discovered what I should really have been listening for all along: musicality. The very fact that I had been so engrossed in the performance told me all I needed to know.

There was another lesson I learned from this experience too. If you asked me to judge how accurate a system reproduces the music, I would have said that the answer lies in how close it gets to the original performance - you have to judge whether it makes the music sound more, or less, like the real thing.

In a recent edition of Stereophile magazine, John Atkinson argues that this theory doesn't "hold together with two-channel reproduction, in which the ambient sound at the original event is folded into the front channels". This argument, he suggests, "is based on a fallacious assumption: that an accurate representation of the original recorded event is encoded in the grooves, pits or bits". And, of course, he's right. You cannot achieve a perfect recording of the original piece any more than a photograph of a Van Gough can be an exact simulacra of the original painting. But this shouldn't necessarily be cause for concern.

Sat there, listening to Miles Davis, it struck me. I wasn't taken away by this performance because I could imagine that he was there in the room. No. I was transported by the music, by this recording. The beauty lay in the performance itself. Russ's system conveys the recording in such a way that all comparisons to other performances of the piece - whether in the studio or the concert hall - seem irrelevant. This was the performance. And it was wonderful.

Perhaps I can clarify this by going back to the analogy with painting. It's like the difference between a reproduction print of a painting and an etching. We need to think of the music we listen to on our Hi-Fi like the latter. An etching is the work or art. It's not a compromised reproduction of an original. The etching was intended right from the start to be the work of art. In the same way, a musical recording is produced specifically to be enjoyed in the home. Taking enjoyment from the experience itself rather than being distracted by comparisons with an unachievable ideal of 'the band in the room' helps to focus the listener on the inherent musicality - or not - of the recorded piece. And that is no compromise.

Originally published in Connected magazine, Issue 25, Summer 2013

Written By Simon Dalton